Laughter beyond fits.

Life, the Universe and Everything is a remarkable book, and not just for the cosmic pull-tab placed so aptly on its front cover. Like its predecessors it is an existential satire with vast and brilliant ideas. Like its predecessors it projects human foibles onto the whole of creation, thence to bounce back in a fatalistic and absurdly funny manner. And like its predecessors it indulges in a digressive, facetious and distinctly Adamsey disregard for the sanctity of traditional prose narrative. Unlike its predecessors it isn’t really a Hitchhiker’s novel.

Capturing the internal zeitgeist of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and The Restaurant at the End of the Universe is, of course, impossible. Almost everyone who’s read Adams has attempted at some stage to do so, and in almost all instances the attempt has proven at least moderately unwise. The person who came closest was – perhaps unsurprisingly, but then again perhaps not, given that he’d written Hitchhiker’s as a duology and that the story wrapped up rather neatly at the end of the second book – Douglas Adams. But even the man himself found it something of a strain to replicate the freewheeling, towel-toting, mind-blowing hoopiness of what he’d set down previously. Less a continuation, more an inspired adlib sucked into the ravenous vacuum of unfulfilled publishing contracts, Life, the Universe and Everything is nothing short of a jump-started series reboot; a greatly laboured-over extemporisation that nevertheless is, as mentioned, quite remarkable.

The full scope of Life, the Universe and Everything is difficult to impart without going into the sort of detail best served by reading the book. The basic storyline, however – the threads of plot used by Adams to connect the various dots and squiggles he’d laid down – is that of the people of Krikkit, a peaceful and isolated race whose sudden introduction to the wider universe provoked in them a xenophobic resolve to wipe out everyone who wasn’t them. Thus came the Krikkit Wars, at bloody culmination of which they and their planet were locked away in a Slo-Time envelope until the end of days. Unfortunately, a cohort of bat-wielding Krikkit robots escaped incarceration and have been roaming the galaxy, ruthlessly reassembling the Wikkit Gate, which is the key to releasing Krikkit from its temporal prison. Should they succeed, the aforementioned end of days will take place somewhat earlier than the rest of the universe would like…

Even for those who know nothing of a Doctor Who pitch that Adams wrote for the BBC during Tom Baker’s ascendency, entitled Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen, this underlying concern of Life, the Universe and Everything seems rather more like a problem in need of solving, Doctor Who style, than the sort of thorny bewilderment that Hitchhiker’s regularly put out there for its quasi-heroes to blunder through, run away from or fail utterly to comprehend or even notice. Adams himself admitted to a certain frustration upon finding that none of his Hitchhiker’s characters were remotely qualified to play the part of the Doctor; yet he persisted and – remarkably – found a way to compensate for and even make a virtue of the dearth of players. Ever the innovator, Adams told the story almost exclusively by way of digressions. More on this shortly.

At the conclusion of the first two Hitchhiker’s books – and also the TV series – Arthur Dent and Ford Prefect are left stranded on prehistoric Earth, wistfully resigned both to the future destruction of the planet and to never finding a satisfactory question to complement the ultimate answer to life, the universe and everything. This is the natural endpoint of Arthur’s journey, and from the unused draft chapters collected in Jem Roberts’ Adams biography The Frood (Preface, 2014) it seems that Adams had tremendous difficulty writing him back into the story. He had, admittedly, done so once previously in Fit the Eighth of the radio series, but only through recourse to a second lightning strike from the infinite improbability drive. Having judged this unsatisfactory, Adams laboured until he came up with a wholly different deus ex machina solution, extricating Arthur and Ford from the antediluvian bathtub of prehistory and dropping them into the middle of Lord’s Cricket Ground just in time for the Krikkit robots’ first explosive appearance. Arthur subsequently travels in the Starship Bistromath (which is powered by restaurant physics), is abducted by Agrajag (a crazed bat-like incarnation of a creature whom Arthur has inadvertently killed many times over on the circle of life), learns how to fly (by throwing himself at the ground and missing), and faces off with a Norse god at an airborne party, none of which virtuoso pieces of Hitchhiker’s lore seem immediately germane to the subject of Krikkit. In fact, Adams appears almost resentful of Arthur’s lack of usefulness, and thus to be punishing him through a barrage of inventiveness that serves only to emphasise the qualities fostering that resentment. Arthur Dent, one of literature’s most passive protagonists, becomes also one of its most passive-aggressive antagonists. Meanwhile, the story itself refuses to unfold. Except…

Somehow, it does. Amidst digressions that seem merely nostalgic, digressions that loop about themselves and come back together like tied shoelaces, digressions within digressions, which transpire to be not just digressions but indeed crucial plot points hiding in brazen anticipation of the big reveal, somehow the story of Krikkit is told. (And by this we mean not just the backdrop of Krikkit – which Slartibartfast exposits shamelessly – but the actual story; the saga of Krikkit once wrested away from the Doctor Who canon and repurposed for Hitchhiker’s.) Arthur Dent remains totally ineffectual, Ford Prefect feckless and hedonistic, Zaphod a restless gadabout, yet through their free-floating conduit and surging by way of discursive slingshot, Life, the Universe and Everything takes on its own unique character. Adams, after dedicating the book, writes that it is “freely adapted” from the radio programme. The two words form at best an infelicitous understatement. In truth, and under cover of its irrepressibly zany content and an overly deliberate, at times predictable stylistic enunciation, the third Hitchhiker’s novel was entirely retrofitted.

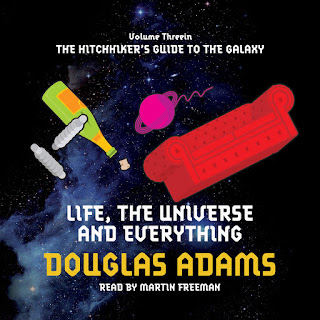

Nowadays, there are several different manifestations of Life, the Universe and Everything to choose from, not least of all an audiobook read by Adams himself (from which was taken his outrageously apoplectic posthumous contribution to the third Hitchhiker’s radio series, voicing Agrajag with lisping, fang-tearing relish in Fit the Sixteenth). One such rendition that adds definitive nuance to Adams’ text is the 2006 audiobook read by Martin Freeman, who in 2005 had played Arthur Dent in the film version of Hitchhiker’s. Not only does Freeman exhibit a well-pitched array of character voices, he brings also a dash of his more assertive film persona to the narration, the story thus coming across almost as if filtered through the perceptions of a more rounded, more self-assured Arthur Dent. If Life, the Universe and Everything has garnered one particular criticism it is that, unlike the seat-of-the-pants exuberance of its much-vaunted predecessors, its word follies, for all their careful construction, feel inexplicably piecemeal. Freeman’s contribution goes a long way towards plastering over the cracks in the façade.

All told (and as frequently related in this review) Life, the Universe and Everything is a remarkable book. Perhaps not wholly remarkable – perhaps not reaching the fanciful heights of perhaps the most remarkable book ever to come out of the great publishing corporations of Ursa Minor – but remarkable nonetheless, and even more so as read by Martin Freeman. Thirty-four years on, pulling the ring-tab will still open to readers a novel of largely unparalleled zest.

No comments:

Post a Comment